How To Explain Anxiety To A Child

For children of any age, knowledge is power. This is so very true for anxiety! In order for children to manage their anxiety, they must have an understanding of what is happening inside their mind and body. Children must be equipped with the knowledge and coping skills in order to move through their anxiety successfully. Anxiety is really not complex, as it is quite predictable and redundant. It is always seeking comfort and certainty. While there are a vast number of reasons that a child may be anxious, the “why” is not really that important. The ideas below are applicable to nearly all triggers of anxiety and for children of all ages. Here are 5 tips on how to explain anxiety to a child.

Normalize Anxiety

This is key to starting on a positive tone. Kids are embarrassed to feel different and alone. They may also be embarrassed to share their personal feelings, as they may think it is a weakness. Due to this, it is important to normalize anxieties with your child.

(Side note, a child may not see themselves as “anxious”. In that case, find out what word is most relatable to him or her. It may be the term fearful, scared, worried, uncomfortable, or nervous. Regardless of the term, they all mean the same thing…anxious!)

Make sure that you share stories of your anxieties through everyday conversations. Children need to see that uncertainties and discomfort happen every day at all different levels. The key here is modeling a positive response to the situations that arise. 65% of children with anxiety have parents who are anxious. As a parent, you must show your child that these daily discomforts and uncertainties are bumps in the road that can be solved without repercussions.

When your child expresses an anxious thought or feeling, make sure that your response normalizes what they are feeing. A child who is worried about the first day of school needs to be reminded that nearly every student is apprehensive about their first day. The fact that they too are feeling this way is normal and expected.

How Anxiety Works

Here is the “meat” when explaining anxiety to a child. As I mentioned in the beginning, anxiety is very predictable, therefore, regardless of the worry, the mind and body respond in the same way. Children scared of storms, large crowds, or germs will all have the same response when their worries are triggered. The “why” or trigger for the anxiety is considered the “content” and is not very important in explaining and managing anxiety.

When explaining anxiety to children, it is important to use the correct vocabulary words. Use real-life scenarios when describing how this process affects them. You can use scenarios that apply to your child or create a scenario that is not the least bit fearful to your child. For example, if your child does not mind bugs and enjoys being outdoors, you may use the example of someone with a fear of bees when explaining anxiety.

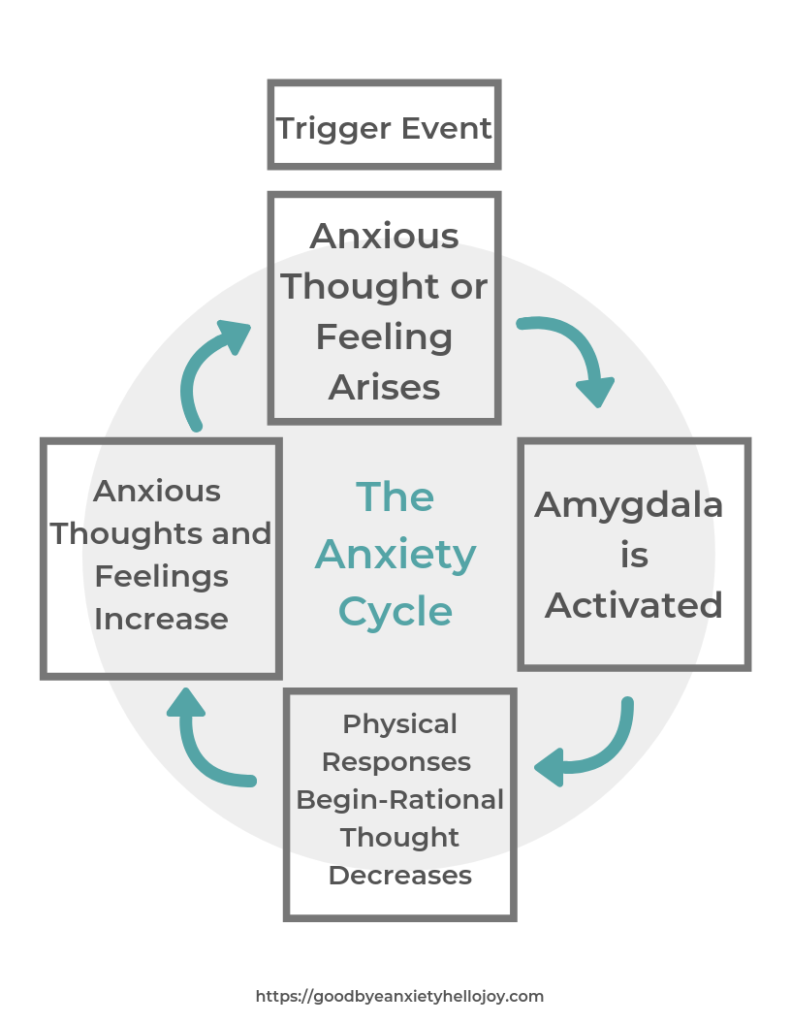

Here is a visual of what happens in your brain when you are anxious. (This is available as a PDF in the freebie library.)

Our brains have a small almond shaped “tool” called the amygdala, which is there to sense danger. It is located deep in the emotional section of our brains (limbic system). Once the danger is encountered, the amygdala fires off the “fight or flight” response as a way to keep us safe and alive. It fires without any thought on our part, which is great in a real crisis. The amygdala is unable to differentiate between real and perceived danger, therefore, signally at any fear, anxiety, or danger.

Of course, we want our amygdala firing off when a bear begins chasing us in the woods or when we need a boost of adrenaline when running in an important track event. However, it becomes a problem when it fires for each and every worrisome thought that enters the brain.

When the amygdala is fired, the prefrontal cortex of the brain, where rational thought and emotional regulation take place, shuts down and your body responds with fight or flight, or survival mode. A child experiencing anxiety at a level that triggers the amygdala is truly unable to think rationally at the moment, making a decision to either fight to get away from the perceived danger or flight to move away from that danger.

Now, use the information you learned above, along with the graphic to show the child how their brain operates without them even having to think about it. Children will understand that they would run away if they encounter a bear. Now, add an example that is more relevant to them, where you see the “fight or “flight” kick in. For a young child, it may be school drop off. Whenever it is time for you to separate from your child, the child chases after you. For an older child it may be when they are to present to their class but instead, go home sick that day.

The problem with anxiety is that it quickly becomes habitual, making you feel ill-equipped to deal with the problem or situation. No child enjoys the feeling of anxiety, so they begin to avoid any situation in which they think that they become anxious. This leads to avoidance, which strengthens anxiety and weakens the child’s confidence in themselves, spiraling to an unhealthy situation. It is necessary to equip children with the idea that by facing anxiety, they can create new habits in the amygdala.

Now, using the examples of the bear, and either the morning separation or the class presentation, explain to your child how, if the encountered a bear frequently when going outside, they would begin to feel scared and eventually chose to stop going outside. Similarly, a child who chases after their parents each morning will continue to do so as the anxiety builds, until eventually, the child may stop going to school because the anxiety hits before leaving the house.

For the older child scared of a presentation, he or she will remember how they felt and left school the first time. They will begin to worry about feeling this way again and avoid presentations that may lead to that feeling. Make sure that child see how their brain thinks that the fear is real because they are responding to and accepting that fear.

Now, here is the great news… Brains are adaptive, meaning that the negative habits creating by “fight or flight’ can be changed. Children can change their response, showing the amygdala that the situation is not really dangerous. It takes bravery and practice but it works really well.

Many children and teens fear that they will lose their ability to be warned of danger are they try to “stop” their anxiety. It is important that children know that the goal is not to eliminate anxiety, but to recognize and manage the anxiety that is not tied to real danger. Through anxiety recognition and management, the amygdala will still do it job or protecting them from real danger but it will not see everything in life as dangerous because they will know how to tell their brain what is a real danger and what is not the real danger.

Externalize Anxiety

This is the next step in understanding and managing anxiety. By understanding how the brain works and why anxiety arises, a child (and their parents) can externalize these thoughts and feelings in order to create new habits for the amygdala. Externalizing anxiety is explained in great detail in The Important of Externalizing Anxiety with a Worry Monster. I encourage you to read this article and work with your child on naming their worry in order to talk back to the anxiety. This ability to talk back to the anxiety is what works to create new habits and teach the amygdala what is real and what is not in terms of danger.

Recognize Anxiety

In order to manage anxiety, a child must recognize that the amygdala has been triggered and they are, in fact, experiencing anxiety. The beginning symptoms for each child will vary, so it is important that a child learn to recognize the ways in which their body responds to anxiety. Symptoms can include rapid heartbeat, sweaty palms, feeling dizzy, upset stomach, and so on. It can also include thoughts that seem to be swirling quickly in the mind or feelings of confusion.

If your child has a difficult time noticing and identifying symptoms within the body, practice with them. Have them sit quietly and guide them to various parts of their body, encouraging them to describe what they are feeling in that particular spot. You can use examples from your own life by telling your child that your stomach feels like butterflies are in there when you are talking in front of other people, or something along those lines.

Facing the Anxiety

Once these feelings, thoughts or sensations begin, and they are identified as the beginnings of anxiety, it is important that a child begins to use the skills that have been taught in order to manage and control the anxiety.

This is where the child must use their skills, along with their brave attitude, to respond in a positive way that shows the amygdala there is nothing to fear. They have learned that avoiding the anxious situation creates heightened anxiety and reinforces the fear as something real and dangerous. It is necessary to do the opposite of what anxiety is telling your child to do.

To do this successfully, a child must expect that a situation, that traditionally evokes anxiety, will, in fact, trigger the anxiety. Since they are now expecting this anxiety, they can talk back to the anxiety, and move into the stressful situation. This should be done with support and in small baby steps. It can feel overwhelming and scary but through positive experiences, the anxiety is lessened and the child becomes more courageous and confident to continue showing anxiety that they are in charge!

Resources to Reduce Anxiety

Children’s literature is a great resource for helping children understand anxiety, see how others handle difficult situations, and to learn coping skills. Here is a list of 8 Helpful Books for Children with Anxiety. Check back as there will be an additional list of books for older children posted soon.

Lastly, this video shows a cat with extreme anxiety when someone enters the room and begins talking to it. This is a great example of what the amygdala does when it senses danger and the child is not telling it that there is no danger. If this cat had skills to manage its uncertainty of someone entering the room, it would not have reacted this way.

Share your experiences below, explaining how your child responded when you explained anxiety to him or her.

Leave a Reply